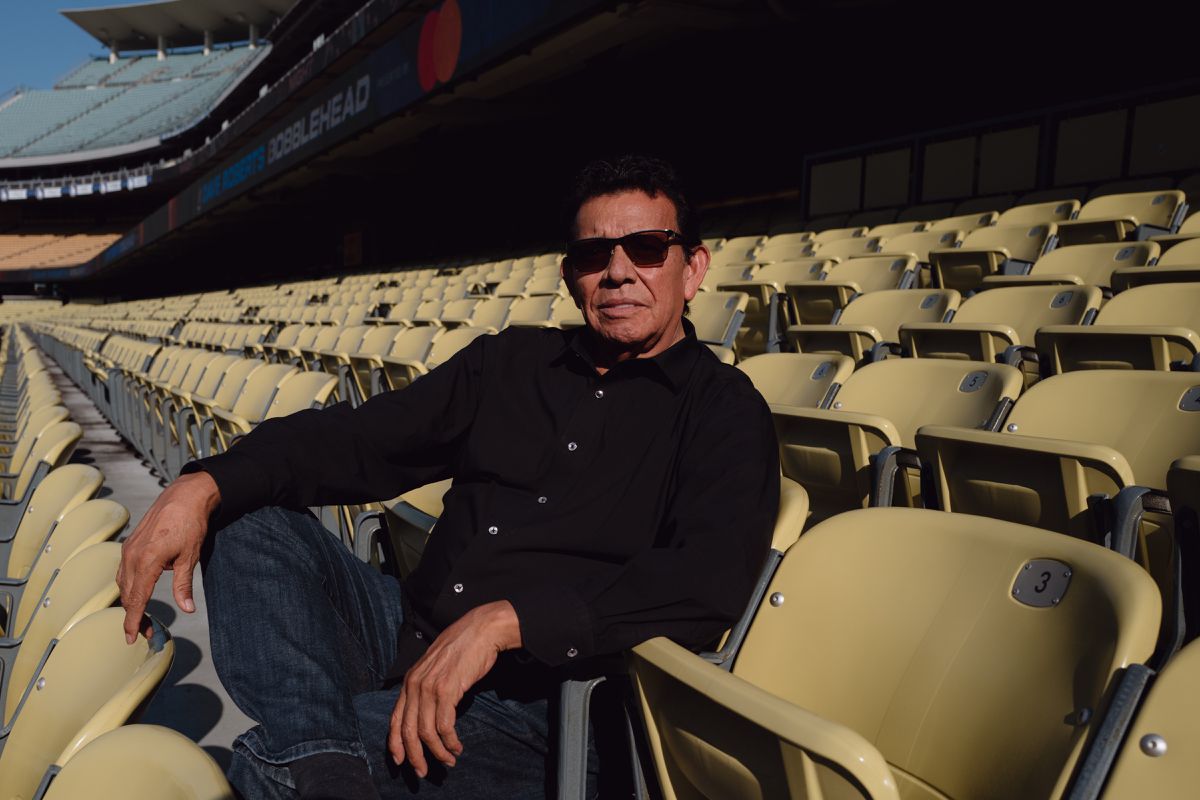

“How do you explain to someone who doesn’t know baseball what Fernandomania is?” The question caused Fernando Valenzuela to look up, recalling the famous move he made to gain momentum on the mound at Dodger Stadium in the 1980s. This afternoon, speaking to EL PAÍS, Valenzuela is not on the mound, but in the bleachers of one of the oldest baseball cathedrals in the United States. “I would say this is the beginning of my career, it happened as a result of all the people following my games,” Valenzuela said humbly. Vin Scully, the legendary Dodgers announcer, was particularly expressive. He described it as “a religious experience” at the time.

This summer brought back those days of euphoria. The Dodgers recently retired the number 34 jersey that Valenzuela made famous because of his left arm. Almost all Dodgers fans acknowledge that the recognition gesture has been a long time coming: it’s been 32 years since Valenzuela called it a day. The delay is due in part to baseball purism, the lore that says only players who are in the Cooperstown Hall of Fame deserve this honor. Valenzuela was not, despite being the first rookie in history to win the Cy Young Award, being an All-Star six years in a row and leaving the Dodgers as the franchise’s eighth winningest pitcher.

“You can see it coming,” said Valenzuela, a man of few words known for guarding his privacy. “No one since that time has worn 34; for me the important thing is that the moment has come. I am very happy.” On the day of the ceremony, he was a bundle of nerves. “I picked the bases loaded and no outs,” he told reporters, eliciting laughter.

Valenzuela has avoided the spotlight for decades. In July 2021, when the Dodgers mark 40 years since their 1981 World Series, he will be the last player from that legendary team to reach the ballpark. He spends his mornings on his other passion, golf. He played 18 holes and headed to Chavez Ravine when he finished. He is now a Spanish-language commentator for the Dodgers’ Spanish-language telecast, providing insight between the first and seventh innings, allowing him to leave the stadium without having to stop every few feet to take in a picture or signing autographs for fans.

The youngest of 12 children from a modest family living in the municipality of Navojoa, in the Mexican state of Sonora, in 2003 – his first year of eligibility – Valenzuela scored only 6% out of 75% votes needed to enter the Hall of Fame. A year later he only got 19 endorsements, ending his chance to become the first Mexican to enter the select group. Whether Valenzuela should be in the Hall of Fame is the subject of endless debate among baseball fans. But the pitcher is at peace with his absence from Cooperstown: “The most important thing for me is the love of the people, the support of all the Hispanic people, not only here in the Los Angeles area, but outside as well,” he saying.

In his book Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers, baseball historian Erik Sherman says Valenzuela’s legacy transcends sports. “[…] he was a healer in a time, like today, where many Americans view Mexicans as second-class citizens. To Latinos he meant what Jackie Robinson was to Blacks,” the author wrote. The humble nature of the pitcher prevented him from claiming such a role in history, but when talking about Dodger Stadium, a building two years younger than him, he noted how things have changed. man. “When I started there were between 6% and 8% Hispanics in the crowd. Now we have 50%. Everywhere you turn you hear Spanish,” he said.

The Dodgers will celebrate Guatemalan heritage on September 20. A few weeks ago, the anthem of El Salvador was played before a game against Arizona and flags decorated the park. In August, the Mexicans were honored. All this would have been impossible if the 18-year-old Valenzuela hadn’t caught the eye of legendary scout Mike Brito. The signing ended in 1979 and Valenzuela’s arm, after a spell in Yucatán in the Mexican league, was experienced in the minors. His momentum reached a fever pitch in 1981. Latinos flocked to see someone like them succeed in the middle of the diamond. This was the end of the bitterness between the Mexican-Americans and the Los Angeles franchise after the decision of the city authorities in 1959 to evict dozens of Mexican families from the land where the stadium now stands. For decades, Latinos have turned their backs on the team. Until Fernandomania came.

“When you are inside the stadium, it is very difficult to accept all the events around you. There were people telling me about some games that I can’t even remember, telling me that people were invested,” Valenzuela said. Among the dates he clearly remembers is October 23, 1981. He started pitcher in the World Series where the Dodgers faced the New York Yankees, who won the first two games of the series at home. Valenzuela pitched in his first World Series, just a few months after his debut. With the help of another rookie, Dave Righetti, and the hitting of Pedro Guerrero, the Dodgers won 5-4 in a game attended by 56,000 people. Five days later, the team won its first title in 16 years after losing four World Series between 1966 and 1978.

“Can you imagine?” Valenzuela asked raising his eyebrows. “In my first year and was in the World Series, against the Yankees! To be a part of it and to win it. There’s nothing like it, it’s the best. ” Another notable night was June 29, 1990, when he pitched the only no-hit, no-run game of his entire MLB career. It took 119 pitches, but he managed to keep St. Louis Cardinals scoreless. In Toronto that day, Oakland Athletics pitcher Dave Stewart did the same against the Blue Jays. It was the first time since 1898 that there were two games in one night.

The Dodgers released Valenzuela in 1991 in an almost dishonorable dismissal. “All careers must end,” said Peter O’Malley, the team’s owner at the time. Valenzuela was signed by the California Angels, who are looking to draw more people to the Anaheim ballpark. To test the left-hander’s level, they asked him to play in the minor league affiliate in Palm Springs. When Valenzuela appeared, there were about 5,000 people waiting for him, which the Angels did not hear. “It wasn’t easy to get there, but that’s what happened. For my style of play I have to be more active and at that time I have to go to the minors to prepare,” he said.

Vincent “Sandy” Nava was the first American-born Hispanic player in the major leagues, making his debut for the Providence Grays in 1882, although he identified himself as more Spanish. During the 1940s there were many Latinos playing ball. Valenzuela is far from being the first Mexican in the sport, but his legacy is one of the most influential.

Today players from the Dominican Republic dominate the major leagues with 90 representatives. They are followed by Venezuela with 53, and Cuba with 20. Mexico has only eight MLB players, behind Puerto Rico, with 19. Why are so few following in Valenzuela’s footsteps? “You have to be a part of a team, so a lot of people don’t become free agents. That made it a little difficult for the Mexican players. It’s not like in other countries, where teams go straight to the player and offer him money. But out of 10, two came first. There is talent in Mexico and lately Mexican players are at the same level as the big leagues,” Valenzuela said.

One of the great Mexican talents in the majors is at its lowest ebb. Pitcher Julio Urías was set to follow in Valenzuela’s footsteps with the Dodgers, but his arrest for an alleged domestic violence incident put his career on edge. This week Urías’ number 7 jersey will be impossible to find in the stadium stores. His image was erased for Hispanic Heritage Month, which began Friday. “He is no longer with the team this year,” suggested Valenzuela, who has never been scandalized in his time as a public figure and has been married for 40 years. “I think the outcome of his hearing should be taken into account,” he added. Urias is scheduled to appear in court on September 27. For now, Valenzuela’s legacy remains elusive.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition