He was named the American League MVP in 1964 and was one of a core of players, including fellow Hall of Famers Jim Palmer and Frank Robinson (no relation), who formed an Orioles dynasty over the next decade as the team reached the postseason six times and the World Series four times.

Although the Orioles lost the World Series to the New York Mets in 1969, Mr. Robinson’s reputation for defensive wizardry was well established by then.

“I’m not going to hit the ball with Robinson in this Series,” said Donn Clendenon of the Mets. “He’s the vacuum cleaner, don’t you know that?”

Among the peak of the career of Mr. Robinson was the 1970 World Series, where the Orioles won against the Cincinnati “Big Red Machine” in five games. Named Mr. Robinson the Series MVP.

He set the tone for the first game, get a groundball in the sixth inning off the bat of the Reds’ Lee May, as his momentum carried him far into foul territory. Mr. Robinson made a whirling throw to strike May first and stop a Cincinnati rally.

“He was heading to the bullpen when he threw that first one,” Clay Carroll, a Reds relief pitcher, said at the time. “His arm went one way, his body another, and his shoes another.”

In the next inning, Mr. Robinson hit a home run to win the game for Baltimore, 4-3.

He continued to make clutch plays in the field and at the plate throughout the five games of the Series. In Game 3, Mr. Robinson jumped to pull Tony Perez’s hard-hit grounder, stepped to third and threw the ball to first for a double play.

In the ninth inning of the fifth and final game, Mr. Robinson made a desperate dive into foul territory to catch a line drive by Cincinnati’s power-hitting catcher, Johnny Bench. Fittingly, Mr. Robinson made the last play of the series on a groundball to third.

In addition to his brilliant fielding, Mr. Robinson hit .429 during the Series, with two home runs and six runs batted in, for one of the greatest performances in World Series history.

“I’m starting to see Brooks in my sleep,” Reds manager Sparky Anderson joked afterward. “If I drop this paper plate, he will pick it up in one jump and throw me back to square one.”

But in all his exploits in the field, Mr. Robinson is less fleet of foot and has an average throwing arm. His strengths are his quick hands, a lightning fast release on his throws and an uncanny ability to anticipate where the ball will hit.

“When I chase a ball, I always think I’m going to catch it,” he told Sports Illustrated in 1969.

Mr. Robinson had his best season in 1964, batting .317, hitting 28 home runs and driving in 118 runs — all career highs — and being named the American League MVP.

Despite winning 97 games in 1964, the Orioles did not reach the World Series until 1966, the year another Robinson – slugging outfielder Frank Robinson – was acquired in a trade with Cincinnati. Frank Robinson, the Orioles’ first Black star, led the league in batting average, home runs and RBIs to win baseball’s Triple Crown. Brooks Robinson drove in 100 runs and was excellent in the field.

Brooks Robinson grew up in Little Rock, where he attended Central High School, the site of violent White protests against federally enforced integration efforts in 1957.

But in Baltimore, Brooks Robinson embraced Frank Robinson from the start, saying the slugger was “exactly what we needed.”

With the two Robinsons, pitchers Palmer and Dave McNally, and Hall of Fame shortstop Luis Aparicio, the Orioles won the 1966 World Series over the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Throughout his career, Mr. Robinson always obliged when asked for an autograph and was even featured in a Norman Rockwell painting, signing a baseball for a young fan. (He writes with one left hand, although he bathes and throws with the right hand.)

“Of all the greats in the game, Robinson is perhaps the least cursed by his own fame,” the Washington Post sports columnist Thomas Boswell wrote in 1977, when Mr. Robinson retired. “He had a lot of talent and he never abused it. He received a compliment, and returned it with common decency. While other players dress like kings and act like royalty, Robinson arrives at the park dressed like a cabdriver. Some stars have fans. Robinson made friends.”

Brooks Calbert Robinson Jr. was born in Little Rock on May 18, 1937. His father, a fireman who played semipro baseball, introduced his son to baseball at a young age, using a sawed-off broomstick as a bat.

Shortly after his graduation from high school in 1955, Mr. Robinson signed with the Orioles, a year after the former St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore. He played briefly with the big league team in 1955, and became the starting third baseman in 1958 before being sent back to the minor leagues the following year.

He became an Oriole for good in 1960 and never played for another team.

During his career, Mr. Robinson set a record for most games played at third base (2,870) and is still baseball’s all-time leader, by wide margins, for most putouts, assists and doubles. games in his position.

Known primarily for his fielding, he finished his career with a lifetime batting average of .267, 268 home runs and 1,357 runs batted in and was quickly elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983, the first year he was eligible. He is a leader of the players’ union, the Major League Baseball Players Association.

In 1959, he met Constance Butcher, a flight attendant on one of the Orioles’ team flights. He told her that all his teammates were married, according to his 1974 memoir, “Third Base Is My Home.”

“So remember,” he added, “if any of them try to talk to you, I’m the only single, eligible bachelor on the plane.”

They got married a year later. Mr. Robinson, who was raised as a Methodist, converted to Catholicism, his wife’s faith. They have four children. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Following his playing career, Mr. Robinson worked as a television broadcaster for the Orioles from 1978 to 1993. He briefly lived in California before returning to the Baltimore area, where he was involved in several businesses, including an oil company, a consulting organization for athletes and minor league baseball franchises. He is the co-author of several books about his baseball life.

He sold most of his memorabilia in 2015, donating the $1.44 million proceeds to a charitable foundation he and his wife started.

In 1991, before the last game at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium – the Orioles’ home park for Mr. Robinson – he threw out the ceremonial first pitch. He was joined by former Baltimore Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas, who threw a football.

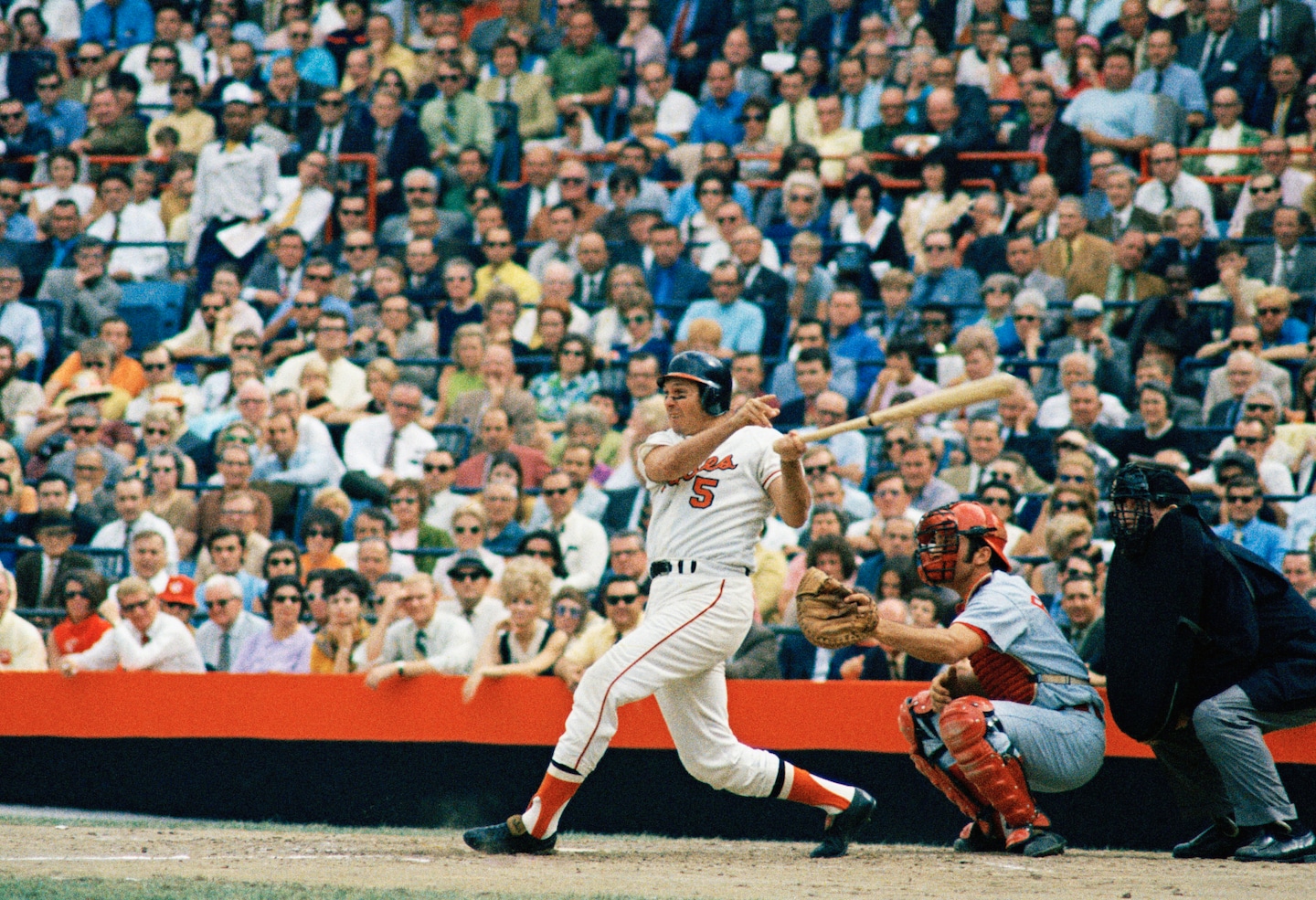

The Orioles retired Mr. Robinson’s No. 5 in 1977, and a statue of him was unveiled outside Oriole Park at Camden Yards in 2011. It depicts him preparing to throw out a runner at first.

“Baseball is the only thing I’ve ever done in my life,” he said in 1969, “and it’s the only thing I’ve ever loved.”